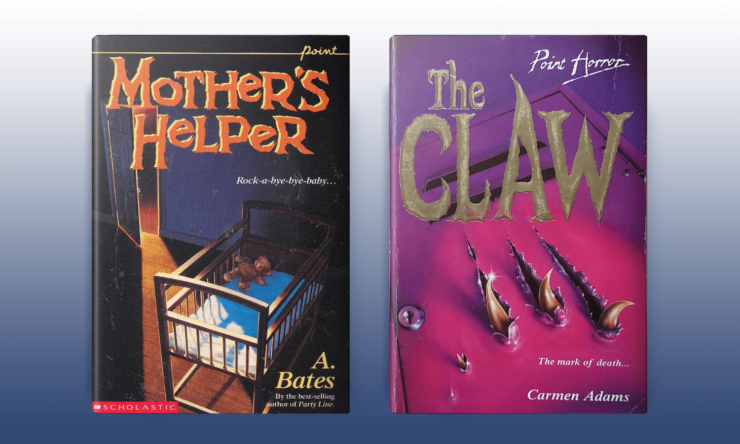

Summer is a great opportunity for teens to get some work experience, finding a part-time job to earn a bit of spending money or landing an internship to add to their college application portfolios. But like everything else in ‘90s teen horror, these jobs are never easy and they invariably come with a wide range of dangers that definitely weren’t listed in the job description. In A. Bates’ Mother’s Helper (1991) and Carmen Adams’ The Claw (1995), their female protagonists find unique and exciting summer jobs that end up being more than they bargained for. Interestingly, while many novels of the ‘90s teen horror tradition lean into the supernatural, Mother’s Helper and The Claw both keep their horrors firmly grounded in the realistic, providing not just thrills and chills, but a glimpse of some of the everyday dangers of the adult world beyond.

In Mother’s Helper, Becky Collier gets a nannying job for an adorable little boy named Devon, accompanying him and his mother to a secluded island off the Washington coast for the summer. Devon is well-behaved and agreeable and while he naps, Becky has plenty of time to work on her tan. But as the summer goes on, she begins to encounter some unexpected challenges: Devon’s mother—who is referred to only as Mrs. Nelson—has a strictly regimented schedule for the baby, disappears for hours at a time for mysterious “meetings,” keeps the only phone in the house behind a locked door, and nearly holds Becky captive, reluctant to let her venture into the nearby town after Devon falls asleep. Mrs. Nelson tells Becky that they must be vigilant about their privacy and Devon’s safety because her ex-husband is threatening her and wants to kidnap the child, an extra layer of stress and responsibility for Becky, who is often home alone with Devon. Becky loves Devon and frequently finds herself taking care of Mrs. Nelson as well, talking her down when she starts getting hysterical and helping her concoct elaborate plans in case her ex-husband turns up, which is definitely above and beyond the standard slate of nannying duties.

Becky makes the best of it and finds various workarounds to cope with Devon’s mother, care for Devon, and even enjoy herself a little bit. She lets Devon feed himself and gives him the vegetables he likes (sweet potatoes) rather than making him eat the ones he doesn’t (peas). She goes along with most of Mrs. Nelson’s restrictions and limitations, though she does stand up for herself and demand permission to occasionally go into town in the evenings to shop for souvenirs for her family and to pick up some library books (which Mrs. Nelson swipes to read herself, but Becky is so generous and good-humored that she doesn’t complain, even when Mrs. Nelson takes the book Becky herself was reading. This is a pretty clear indicator that Mrs. Nelson is not to be trusted and might be a horrible person). Becky even meets a mysterious young man named Cleve, who offers to show her around town and take her out for ice cream. Becky takes him up on this because he’s cute, even though she’s not supposed to talk to anyone on the island, because Mrs. Nelson is worried that her husband might have spies looking for them, though between Cleve being a local islander and Mrs. Nelson watching all the boats and ferries that arrive at the island (her mysterious “meetings”), it’s not entirely clear how realistic of a danger this is. Becky’s attraction to Cleve gets even more complicated when the local sheriff falls down a seaside cliff and is injured, with lots of people saying Cleve pushed him.

Buy the Book

Just Like Home

It quickly becomes apparent that Mrs. Nelson isn’t who she says she is. First of all, she has stolen Becky’s identity and used the girl’s name on all of the paperwork necessary for their vacation home and their summer needs, including the rental agreement for the cabin, the order form for a washer and dryer that she has delivered, and the bank account she’s using to pay for it all. There are a lot of red flags here, obviously, not the least of which is the fact that at seventeen, Becky’s signature on a contract wouldn’t be legal. The even bigger bombshell is that Mrs. Nelson is not trying to protect Devon from being kidnapped: she actually is his kidnapper, having taken him from her ex-husband and his new wife, telling Becky that Devon “should have been mine” (156), as if that makes it all okay. Despite all of these complications, Becky’s driving motivation remains keeping Devon safe and she adjusts to reality as she learns it to make the right choices for him, getting him safely back to his father. Mrs. Nelson manipulates Becky, hits her over the head a couple of times, and attempts to blow up the cabin with Becky inside, though in the end Becky still finds that “she felt a pang of sympathy for Mrs. Nelson” (163), unable to hold a grudge or wish her ill even after her lies and multiple attempted murders.

Becky is maternal and virtuous, and in the end she is richly rewarded: Mr. Nelson gives her a big check as thanks for returning his son and offers her a lucrative nannying job for the next summer as well, in a big house with a swimming pool and horses, a definite step up from a secret cabin in the woods. It also turns out that Becky and Cleve (who didn’t push the sheriff off the cliff, of course) make a pretty good team and she scores herself a boyfriend too, though whether he’s a prize is up for some debate. Cleve is paternalistically protective, fussing over Becky and telling her not to go after Mrs. Nelson in their final confrontation (Becky does anyway), and while he temporarily hides Devon when Becky needs him too, he’s not particularly happy about it, telling her “Don’t ever do it again, please! Babies and I do not get along” (163), unconvinced when Becky tells him that she’ll be happy to teach him how to interact with and take care of children.

Becky’s a bit too nice and in the novel’s final lines, she’s recovering from her head injury and at peace with what happened, wanting only the best for Devon, his family, and even Mrs. Nelson as “It didn’t matter, she wished them all luck” (164). This neatly tied up conclusion feels disingenuous, given that Mrs. Nelson still hasn’t been found, still believes she has a right to claim Devon, and has proven herself capable of subterfuge and violence, but apparently as far as Becky is concerned, all’s well that ends well. Maybe the residual effects of her head trauma are clouding her thinking.

In Carmen Adams’ The Claw, Kelly Reade and her friend Rachel McFarland encounter a different set of summer job challenges when they score coveted internships at Creighton Gardens, their local zoo in Danube, Illinois. These internships are competitive and it seems like the chance of a lifetime; as Rachel tells Kelly, “it’s pretty incredible – what with all the science nerds, and premed types, and just in general animal lovers who want to get in every summer – that both you and I made it” (3). The competition for spots may be legitimate, but there’s also quite a bit of nepotism involved as well, as two of the six summer interns have parents connected with the zoo, one on the board of directors and the other the zoo’s chief financial officer. The interns get the opportunity to try out a wide range of zoo duties, from working the snack bar to helping in specific animal enclosures. Kelly and Rachel are assigned to the big cats, while other interns assist keepers working with bears, birds, giraffes, antelopes, and primates. But right from the start, there’s something weird about this internship, beginning with the anonymous phone call Kelly gets before their first day, telling her that “My advice is to stay away. Girls can get hurt in zoos” (7, emphasis original), which is followed by a note a couple of days later, advising her to “Be careful. Don’t turn your back on large animals. Cages don’t always hold” (25, emphasis original). This warning proves warranted, when someone lets the zoo’s black leopard out of its cage and it runs loose around the town, even attacking Sandy, one of their fellow interns, before it is recaptured.

The town is in a tizzy over the escaped black leopard, with sensationalistic news coverage and widespread hysteria, but it turns out that the big cat is the very least of their worries. As they eventually discover, the real culprit is Melissa, one of their fellow interns and the daughter of the zoo’s chief financial officer. Her father had been embezzling from the zoo and was about to get busted, so she let the black leopard out of his cage to incite panic and a wave of bad publicity for the zoo, as well as to delay the upcoming audit that would reveal his criminal activities. Melissa was also responsible for a number of occurrences that were blamed on the black leopard, including paw prints outside of Kelly’s basement window, scratches on fellow intern Griffin’s car, and scratches on her own employee locker which are intended to throw suspicion off of herself.

Beyond Melissa’s sabotage, however, Kelly and Rachel’s lives are shaped by a wide range of real world threats and problems. In the novel’s opening pages, Adams almost immediately acknowledges the racism that Rachel faces as one of the only Black girls in their small town. As Rachel tells Kelly, in her first interaction with Melissa the other girl commented on how “it was ‘terrifically enlightened’ of the zoo to have hired such a ‘racially balanced’ mix of interns. Meaning me and Sandy Lopez” (18). Race is rarely addressed so directly or critically in ‘90s teen horror, so this is a refreshing conversation, though this critique is compromised when Kelly responds “why does that make you upset? Maybe she meant it … You’re being paranoid” (18). Rachel takes the microaggression of her friend’s doubt in stride, correcting Kelly and validating her own perception of and emotional response to Melissa’s comments, and hopefully this helps shift Kelly’s perspective, though readers don’t see any immediate evidence that that’s the case.

With the zoo being the central setting of The Claw, Adams also takes the opportunity to briefly address the ethical implications of holding animals in captivity. Kelly emphasizes the importance of human responsibility, explaining that “We’ve been encroaching on their territory, using up their space, poisoning their water. They should be really mad at us humans” (24). Lonnie Bucks, the keeper who looks after the big cats, has an empathetic relationship with them, lamenting that “Animals in cages is a sad business” (33), though he later amends that a world where the big cats are free to roam is unattainable, as “Cats don’t have their freedom in the wild anymore. People are hunting them, their land is shrinking. They don’t have enough to eat or drink. Which is worse, I ask myself – that or this?” (172). At the end of The Claw, there are no major systemic changes in the zoo’s structure of functioning, but Kelly, Rachel, and at least some of the other interns have a better understanding of and greater empathy for the animals they encounter in captivity at Creighton Gardens, and an awareness of their role in and responsibility to wildlife in the world beyond (though much like Rachel’s experiences of racism, these moments of critical engagement are embedded in the larger narrative, rather than presented as central points in their own right).

Finally, Kelly has some significant challenges at home, too, as her older sister Heather has run away and her parents are working hard to find her. While this remains a peripheral side story in The Claw, Adams presents a world that isn’t necessarily safe for or particularly concerned with the well-being of young women, who can disappear and be exploited with little recourse. In the end, after months of searching and the use of a private detective, they find Heather, who has fallen in with a cult-like group in California, and they are able to bring her safely home. As Heather tells Kelly, “I got a little lost. There are lots of souls out there, all of them searching. And there are people who take advantage of that” (176). There’s definitely a long road ahead for Heather and her family, though for the time being, Kelly is content with knowing that “she would hear more later when Heather was ready to talk” (176), just glad to have her sister home and her family reunited.

Kelly fares much better at the end of The Claw than Becky in Mother’s Helper. Kelly has also met a cute boy (Griffin), though when he tries to tell her what she can and cannot do in a misguided attempt to “protect” her, she tells him exactly where he can get off, making it clear that she is going to make her own decisions and theirs will be a relationship of equal partnership, or they won’t have one at all. Kelly comes up with the ingenious plan to trap Melissa, which involves her hanging out in the guest area of the big cat house alone for two nights in a row as bait, a challenge she bravely rises to meet. She is confident in her ability, strength, and heroism, and doesn’t feel the need to brag about her exploits, thinking to herself that her family “didn’t need to know they had Wonder Woman under their roof. Yet. She’d tell them sometime. For now, it was enough that she knew it” (177).

In both Mother’s Helper and The Claw, these teenage girls find summer jobs that end up teaching them what they’re capable of, the lengths they will go to protect others, how to respond to dangers and injustice in the world around them, and their capacity for standing up for themselves and making their own choices. Becky and Kelly have two really different experiences and are two very different people, but both have been profoundly shaped by their summer work experiences, with lessons learned, relationships built, and a better sense of what they can survive and the challenges they can overcome.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.